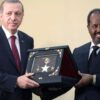

In recent developments, Ethiopia and Somalia have reached an agreement in Ankara, facilitated by Türkiye. This agreement, which comes as part of Türkiye’s diplomatic efforts to mediate the crisis between Somalia and Ethiopia over Somaliland, raises several critical questions about the role and efficacy of the Somali government. As the foreign ministers of both countries convened with Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Hakan Fidan, the memorandum of understanding they signed highlighted significant concerns and potential repercussions for Somalia.

First and foremost, the deal struck between Ethiopia and Somaliland on January 1, granting Ethiopia rights over 20 kilometers of Somaliland’s coastline for 50 years, is a pivotal issue. This agreement, which also includes access to Berbera Port, has significant implications for Somalia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. Why was Somalia seemingly sidelined in such a crucial agreement that directly affects its territory and strategic interests? The Somali government’s apparent lack of proactive engagement and assertiveness in this matter is troubling.

Moreover, Ethiopia’s initial move to recognize Somaliland, although later clarified as not being formal recognition, still poses a fundamental challenge to Somalia’s claims over the region. How did the Somali government allow the situation to escalate to this point without foreseeing the potential diplomatic fallout? The government’s reactive rather than proactive stance in international diplomacy is evident and concerning.

The involvement of Türkiye as a mediator, while commendable, also brings to light the question of why Somalia could not resolve this issue through its diplomatic channels. Why did it take external intervention to bring the parties to the negotiation table? This dependence on third-party mediation reflects poorly on Somalia’s diplomatic strength and raises concerns about its capability to handle sensitive geopolitical issues independently.

Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan’s remarks emphasized Türkiye’s dedication to peace, diplomacy, and goodwill, alongside the deep-rooted relations and extensive cooperation with both Ethiopia and Somalia. However, this underscores a broader issue: Somalia’s reliance on external actors to navigate its diplomatic challenges. The Somali government’s lack of a robust foreign policy strategy seems evident, and this dependency might have long-term implications for its sovereignty and regional standing.

Furthermore, the joint statement issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Türkiye detailed the discussions facilitated between Ethiopia and Somalia, noting the exchange of views in a sincere, friendly, and forward-looking manner. However, the effectiveness of such discussions remains to be seen. How committed is the Somali government to ensuring that the outcomes of these talks truly reflect and protect its national interests? There is a pressing need for Somalia to assert itself more vigorously in these negotiations to safeguard its territorial claims and strategic interests.

The second round of talks, scheduled for September 2, presents an opportunity for Somalia to re-evaluate its approach and strategy. Will the Somali government take this opportunity to assert its position more firmly and ensure that its voice is not overshadowed by more assertive counterparts? The future of Somalia’s territorial integrity and its relations with neighboring countries heavily depend on the outcomes of these negotiations.

oaiRZLOVEqQrhdBU